Dive Brief:

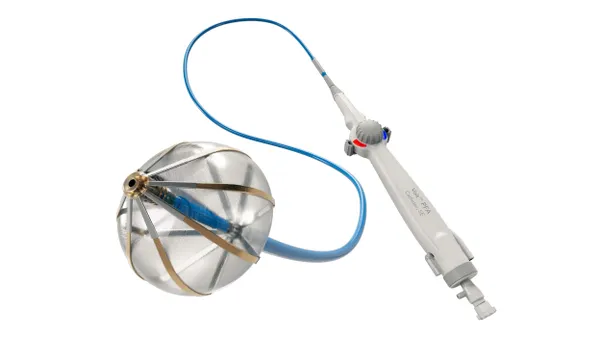

- Five years after undergoing aortic valve replacement, intermediate-risk patients who received an Edwards valve through a transcatheter approach saw no significant difference in incidence of death or disabling stroke compared to those who had more traditional open surgery. That's according to new results from the Edwards-sponsored PARTNER 2 trial published in The New England Journal of Medicine on Wednesday.

- Patients who received transcatheter aortic valve replacement with Edwards' Sapien XT valve more often had mild paravalvular aortic regurgitation and aortic valve reinterventions and re-hospitalizations. TAVR and open surgery appeared to result in similar disease improvements and quality of life outcomes.

- Separately, a pair of cardiologists in an editorial published this week in the journal Circulation argued there may be "important differences" between Edwards' newer Sapien 3 and Medtronic’s CoreValve devices.

Dive Insight:

Major TAVR player Edwards predicts the market will grow to $7 billion by 2024, a forecast Moody’s recently called “plausible.” That scenario is underpinned by the expectation that TAVR will be used to treat more low-risk patients going forward.

One key rationale for TAVR is lower costs for hospitals, so the finding on more repeat hospitalizations and other serious side effects could be worrisome for devicemakers.

The 5-year review of nearly 2,000 patients in the PARTNER 2 trial was inspired by the "scant data" on bioprosthetic valve function and long-term clinical outcomes for TAVR versus surgery in patients with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis, according to study authors.

Long-term follow up extended to 91% of the TAVR participants and 81.4% of the surgery group. At five years, one-third of patients in the TAVR group had at least mild paravalvular aortic regurgitation, which has been associated with increased risk of death. Comparatively, patients who had open surgery had incidence of just 6.3%.

Additionally, repeat hospitalizations occurred for one-third of the TAVR group, versus about a quarter of the surgery group. A little more than 3% of TAVR patients had aortic valve reinterventions, which happened in less than 1% of open surgery recipients.

The authors noted in discussion that between two and five years post procedure, there was a higher incidence of disabling stroke and death from any cause among TAVR patients, which could be attributed to the more common moderate or severe paravalvular regurgitation or a higher rate of significant, untreated coronary disease.

A limitation of the study's results is the fact they're based on patients who received Sapien XT, an Edwards valve no longer in clinical use, the authors said. "The currently used SAPIEN 3 valve, which incorporates an external sealing skirt and is implanted with the use of CT sizing, is associated with markedly lower incidences of postprocedural and 1-year moderate or severe paravalvular aortic regurgitation than were seen with previous-generation devices," the study said.

Edwards is going toe to toe with Medtronic for the fast-growing TAVR market. However, physicians faced with the decision about which device to choose lack much directly comparable data. An editorial published this week in American Heart Association journal Circulation responded to findings from two registry studies originally presented late last year aiming to fill that head-to-head data gap.

The studies suggested Edwards’ balloon-expandable technology may yield better outcomes than Medtronic’s rival approach. While the difference may be due to confounding variables, the authors suggest it could equally reflect the effects of the devices themselves.

One study linked Edwards’ Sapien 3 to lower rates of all-cause death, cardiovascular mortality and other negative outcomes. The other, smaller study found patients treated with Sapien 3 were less likely to suffer from paravalvular regurgitation, in-hospital mortality or die within two years.

The authors of the studies cautioned against reading too much into the findings, as did the editorial published at the same time. That reticence to draw firm conclusions reflects the potential for factors other than the effects of the devices themselves to drive the divergent outcomes.

A second editorial published in Circulation this week raised similar caveats, stating “clinical features certainly play some role in the selection of valve type for different patients.” Exactly what role those features play cannot be determined in registry studies. Yet, despite those caveats, the authors of that editorial think the registry data may reflect actual differences between devices sold by Edwards and Medtronic.

“Although these data should not be used in isolation to conclude that balloon-expandable valves are the superior option for TAVR, they do raise the possibility that important differences may exist in patient outcomes related to valve choice,” two U.S.-based cardiologists wrote in the editorial.

Whether important differences do exist is unlikely to become apparent until TAVR devices are pitted against each other in adequately powered randomized controlled clinical trials. The cardiologists who edit Circulation highlighted the need for such studies but companies typically lack enough financial incentives to carry out big head-to-head trials.