The U.S. Commerce Department’s Section 232 investigation into semiconductor imports could create substantial new costs for the medtech sector if it brings additional tariffs, especially for medical devices that are chip-intensive or produced at a large scale, according to experts who spoke with MedTech Dive.

President Donald Trump’s tariffs are already causing financial fallout for device makers. In first-quarter earnings updates, companies such as GE Healthcare and Thermo Fisher cut full-year profit forecasts, while others like Johnson & Johnson and Danaher warned they expect several hundred million dollars in tariff-related costs.

Tariffs on semiconductors could raise input costs for medical device manufacturers, yet companies may not be able to pass those costs on to customers immediately, said Scott Almassy, consulting firm PwC’s U.S. semiconductor leader. Device makers often work with long planning cycles and tight cost controls.

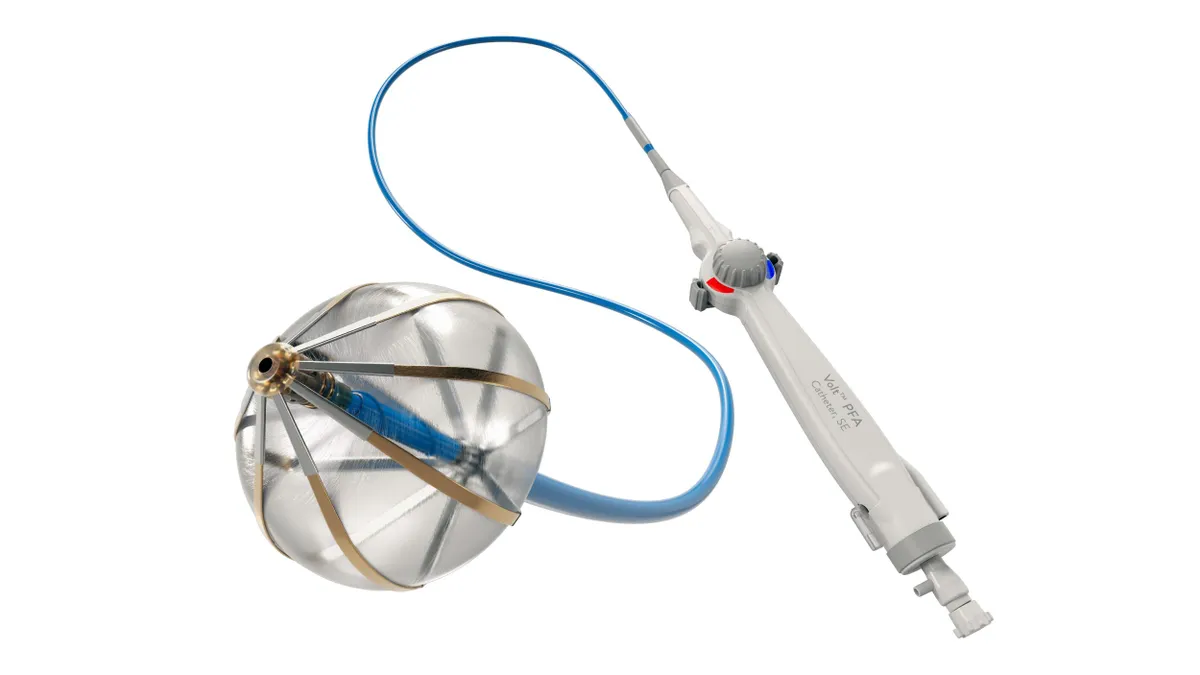

“For devices that depend heavily on advanced chips — such as implantable monitors, imaging systems, or AI-driven diagnostics — the cumulative cost impact could be meaningful,” Almassy said via email.

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick is assessing the effects on national security of importing semiconductors, semiconductor manufacturing equipment and derivative products, which contain semiconductors, according to a federal notice on the investigation, conducted under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act.

Medical devices could be considered derivative products under this framework, Almassy said, adding that the bulk of medical-grade semiconductor manufacturing occurs overseas, primarily in East Asia, including Taiwan, South Korea and China.

The Section 232 probe will look at whether dependence on foreign sources for semiconductor chips has national security implications, said Harvard Business School professor Willy Shih, who noted semiconductors are widely used in medical devices of all types.

Competing for chips

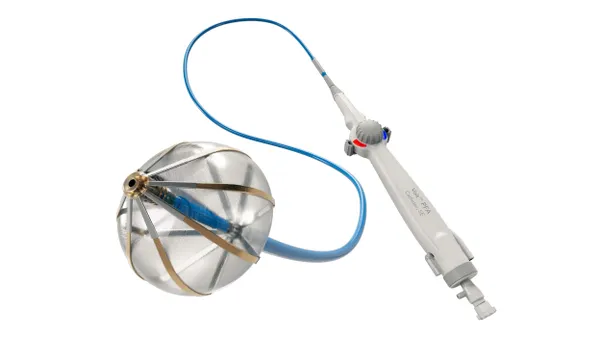

The medtech industry raised alarms about semiconductor shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Semiconductors are found in everything from robotic surgery and diagnostic assay systems to pacemakers and defibrillators, ventilators and devices that monitor glucose, oxygen and blood pressure. Even so, trade group AdvaMed said in 2022 that the medtech industry comprised just 1% of the total semiconductor market and could not compete for access to chips with bigger users such as the auto and computer industries.

AdvaMed did not respond to MedTech Dive’s request for comment for this story.

Congress set out to boost domestic semiconductor manufacturing with the passage of the CHIPS and Science Act in 2022, authorizing $52 billion in investments and incentives. The Trump administration has also made accelerating investment in U.S. production of semiconductors a priority.

Companies have taken proactive steps to rebuild inventory, diversify suppliers and improve supply chain visibility, PwC’s Almassy said, but semiconductor lead times haven’t fully recovered across all medical device categories.

Lian Yang, a partner at the law firm Alston & Bird, said Trump has favored the use of Section 232 investigations as the basis to target specific industries for tariffs, starting with steel and aluminum during his first term, and the authority has withstood court challenges. Section 232 probes have been opened for sectors including automotive, copper, lumber, pharmaceuticals and critical minerals. Completed investigations have led to tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum and cars and auto parts.

The impact on medtech companies from potential semiconductor tariffs could be substantial, Almassy said, with even small increases in component costs having outsized effects on margins when absorbed across large product volumes.

“As devices become more digitized and software-driven, the reliance on semiconductors will only increase,” he said. “These components are not just part of the device — they enable the device.”

With the medtech industry already under pricing pressure from payers and providers, the added costs could mean tighter margins and reduced flexibility in product development or commercial investment, said Almassy. Localizing chip production could help insulate companies from geopolitical disruptions and supply chain volatility, he said, but reshoring is capital-intensive and may increase costs in the short to medium term.

Lobbying effort

AdvaMed has repeatedly pressed the Trump administration to exempt medical devices from tariffs to no avail, most recently calling for a reciprocal “zero-for-zero” tariff agreement on medtech.

Almassy said critical health infrastructure such as MRI machines, CT scanners and ventilators could have a stronger case for tariff exemptions because of public health needs, and specialized semiconductors like those used in implantable devices or critical care monitors might also be considered for targeted relief. However, Trump wants to bring manufacturing back to the U.S., and PwC’s analysis points to fewer tariff exemption carveouts.

The general trend “is toward a narrowing, not a broadening, of exemption policies,” Almassy said.

Section 232 probes must be completed and a report issued within 270 days. The Commerce Department is asking for the public to submit comments on the semiconductor investigation by May 7.