When monkeypox cases in New York started to increase in July, Robert Pitts was tapped to lead the response team at NYU Langone Health’s Bellevue Hospital in New York City. He quickly realized that testing resources were scarce.

“Access to testing is just so limited,” the infectious diseases specialist said. “There are testing facilities that are available. Just the process to actually get testing has been very, very challenging.”

Even as commercial laboratories have ramped up testing capacity, patients still face several barriers. To make monkeypox tests easier to access, physicians say more staffing for diagnostic sites is needed and new types of tests could be a helpful tool in the response.

The U.S. declared monkeypox a public health emergency on Aug. 4, and as of Aug. 9, there were 9,492 cases in the country, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Patients sometimes experience flu-like symptoms like fever or aches a few days before developing a rash. The virus largely spreads through skin-on-skin contact, but also can spread through contact with respiratory droplets and touching objects that have been used by someone with monkeypox such as clothing or towels, according to the CDC. Anyone can get monkeypox.

Access to testing isn’t only critical to slowing the spread, but also to ensuring patients can get access to treatment, experts say.

For example, if a patient has painful lesions causing proctitis, or lesions around their eyes or esophagus, they could meet the criteria for treatment with antiviral Tecovirimat, also known as Tpoxx. The drug is approved to treat smallpox, which is in the same family of viruses, although it has not been specifically approved for monkeypox. Clinicians need to either have direct contact with the CDC or an institutional review board and put a patient on a treatment monitoring protocol, Pitts said.

“Patients often have lesions all throughout their body. Some can have pain, discomfort and may not be eligible for monkeypox treatments and still need pain management,” he noted. “The patients I’ve taken care of have so many questions, like when can we come out of isolation and when are their lesions going to heal.”

While the public health emergency can be used to expand access to vaccines and treatment, more testing resources are also needed, according to disease experts.

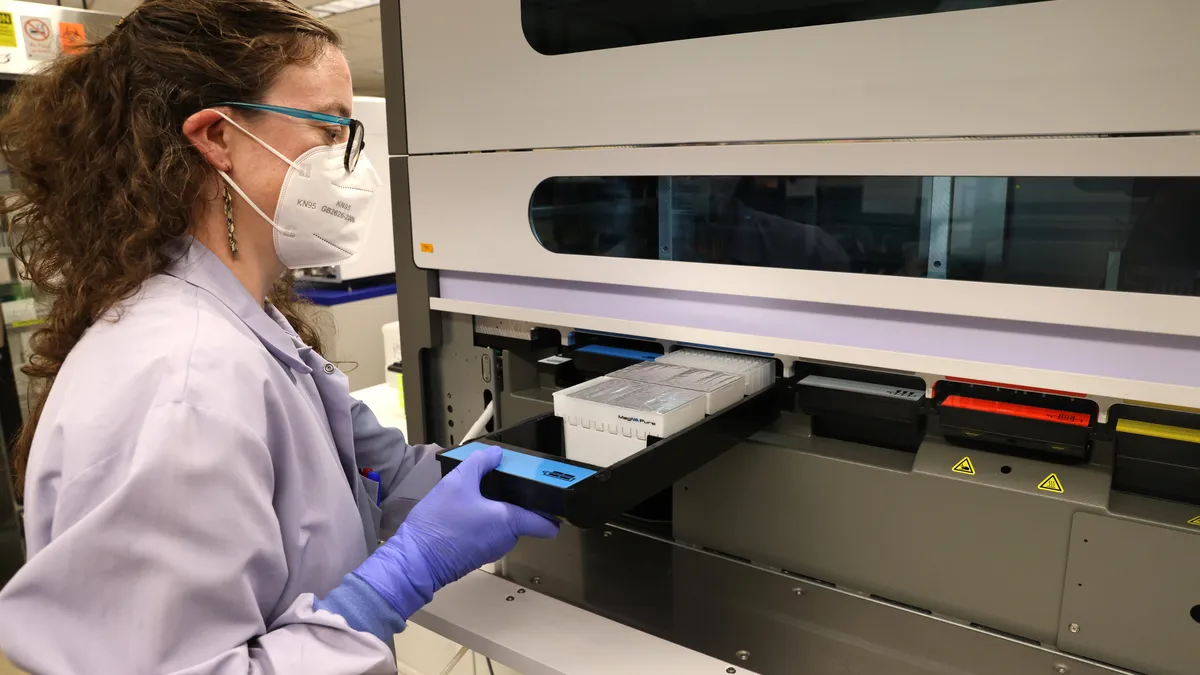

Building testing infrastructure

The early response draws some parallels to the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic, although an FDA-cleared test for monkeypox already existed before the current outbreak. At first, the CDC’s test was only available through a network of public health laboratories, which was difficult for doctors to access.

“It’s the same problem that happened with COVID-19. This is exactly identical,” said Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore. “Eventually the government relented and said commercial labs can do the tests. Once that happened, testing has become easier.”

Bringing on five commercial laboratories ramped up testing capacity to about 80,000 tests per week, while only a fraction of that capacity currently is being used. Patients now are facing challenges in accessing the tests as health systems lack the staffing and resources to manage testing programs.

“Right now there’s a lot of confusion in the community about where to get tested, where can people find treatment,” said Pitts at NYU Langone Health. “There's just no clear guidance because I think a lot of the different facilities and health care systems in New York are still trying to patch together pathways.”

With the COVID-19 pandemic, Pitts said he had funding, dedicated staff and space for testing. It’s a different story now.

“For monkeypox, that is not true at all. We’ve had to borrow space, borrow staff, which has been really, really challenging,” he noted.

To be able to provide testing, the site is taking two mid-level primary care providers out of their normal clinical responsibilities. Every day, Pitts dedicates about four to five hours of his time to monkeypox.

“And so I'm using my own time, because it’s a crisis, to respond to it,” he said.

Dr. Syra Madad, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Harvard Kennedy School's Belfer Center in Cambridge, Mass., added that the increased testing capacity was “welcome news,” but having a test and making sure it’s being used are two different processes.

“If we've learned anything from the COVID-19 pandemic, it's that last mile that you really need to make sure you're working very hard and fast on,” Madad said.

Developing new tests

Currently, four of the five commercial testing companies are running the CDC’s monkeypox test. It uses a skin lesion swab to detect non-smallpox orthopoxviruses, the family of viruses that monkeypox belongs to. The fifth company, Quest Diagnostics, is offering its own lab-developed test that can detect the specific monkeypox virus that is related to the current outbreak. According to an Aug. 5 press release, the company also is working to validate the CDC’s test with plans to offer it in the first half of the month.

Other companies also are developing their own monkeypox tests.

For example, Roche developed three PCR tests for research use, which generally use a skin lesion swab, although sample types can vary according to clinical presentation of the patient, the company wrote in an email. Abbott Laboratories and Becton Dickinson also have developed their own PCR tests for research use.

Although Labcorp currently only offers the CDC’s test, the company is “aware that other testing options are being evaluated for possible use in the future,” Chris Allman-Bradshaw, director of media relations, wrote in an email.

Currently, no tests that use saliva swabs or at-home tests are being offered in the U.S.

Lab-developed tests for monkeypox were subject to “enforcement discretion,” meaning the FDA didn’t require clearance or authorization prior to them being marketed, Tim Stenzel, director of the FDA’s office of in-vitro diagnostics, said at a July 27 testing town hall. Now that the outbreak has been declared a public health emergency, the Department of Health and Human Services can give the FDA authority to issue emergency use authorizations for diagnostic tests and treatments.

If that happens, the FDA plans to require that all makers of monkeypox tests — including lab-developed tests (LDTs) — seek emergency use authorization, FDA spokesperson Abby Capobianco wrote in an email. However, the agency plans to let labs that are currently using LDTs to test lesion swabs to continue testing.

In a July safety communication, the FDA warned that swab samples should only be taken directly from skin lesions, not from saliva or other sources.

However, Madad said it could be helpful to develop new tests that can use throat swabs, for example. She also sees an opportunity for rapid antigen tests or lateral flow tests.

“It's kind of a spectrum of disease and with monkeypox, when you have those skin lesions present, that means you're already well into your course of illness with this disease, so we're not catching it on the onset of the illness,” she said.

It’s not yet clear if the virus can spread without symptoms or before they appear, but it’s a research priority, Madad added.

At-home testing

David Stein, CEO of at-home testing startup Ash Wellness, sees an opportunity for at-home testing to improve access.

The New York-based company is working with laboratory testing partners to bring at-home testing kits for monkeypox to its platform. Stein said they would work similarly to the test developed by the CDC, but patients would collect a sample at home and mail it to a laboratory. The tests are still being validated, he added.

Stein has heard stories from friends who are unsure where to get testing. Until recently, urgent-care centers and major health systems didn’t know where to direct them.

“What I've heard anecdotally from friends, is that if they are having symptoms, they’re pretty unsure where to go. Even when they ended up at those different places” they didn't know where to get a test, he said.

For Belfer Center’s Madad, the bottom line is that testing infrastructure needs to increase.

“As the epidemic expands, more and more people are going to require testing,” Madad said. “Having testing more accessible in the community certainly would be a significant contribution to helping curtail this epidemic.”