Like smartphones upended everyday tasks from communication to shopping, artificial intelligence promises to change how the pharmaceutical industry discovers drugs, carries out R&D and even commercializes products.

Before that happens, though, the industry needs to figure out precisely what AI means and how much investment will be required.

Further challenges include trepidation about how best to prove it works and confusion over its power. According to a survey of over 12,000 participants conducted by consultancy PwC in 2016, lack of trust and a need for the human element were the biggest hurdles to using AI in healthcare.

"I don't think artificial intelligence is really here; it's more augmented intelligence. Some high tech people might argue otherwise, but certainly for the pharma industry AI is using technology and algorithms to interrogate data and suggest decisions," said Pamela Spence, EY's global sector leader for life sciences.

The distinction between pure AI, where computers work without human input, and augmented intelligence, where algorithms, data processing and machine learning help humans make decisions is a key one, according to Spence.

The age of killer robots may be less reality than fiction, but as Spence pointed out, pharma is a long way off from true unaided artificial intelligence. Both industry and regulators are still more comfortable with augmented intelligence.

One reason stakeholders are treading lightly is that AI technology is still in early phases, at least when it comes to healthcare and biopharma. In addition, pharma can be slow to adopt new technologies.

But that isn't stopping exploration across a wide range of use cases.

AI has the potential to analyze large swaths of data to match an HIV patient with the most appropriate drug cocktail. On the other end of the spectrum, AI could be tapped to wade through reams of data churned out in drug discovery to find better drug targets.

The technology can be used to look at medical images and detect signals the human eye might never see. In fact, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first product to use AI — a medical device that detects diabetic retinopathy — in April. The product works by using software to analyze patient images and determine whether the patient should seek further medical attention or hold off and be screened again in a year.

Exploration

Pfizer is one of the companies investing heavily in AI, aiming to use it across the value chain. (The pharma wouldn't quantify its bet.)

The company has been working with IBM Watson to identify better targets for cancer during the discovery phase. Pfizer paired up with the famed Jeopardy contender in December 2016 to use "Watson's machine learning, natural language processing, and other cognitive reasoning technologies" to find new targets, determine better drug combinations and create patient selection strategies for immuno-oncology.

According to the company, the average researcher reads 200 to 300 articles in a year, while Watson has "ingested 25 million Medline abstracts, more than one million full-text medical journal articles and four million patents" at the time of the collaboration announcement.

Pfizer isn't the only pharma that has worked with IBM Watson — Novartis, Lundbeck and Teva Pharmaceuticals are among the others. Novartis signed up in June 2017 to use real-world patient data in hopes of discovering better outcomes for breast cancer patients, while Lundbeck tapped the technology in February 2017 for work in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Teva expanded an existing collaboration in 2016 to find better ways to manage chronic disease.

Since then, however, Watson's abilities have come into question, particularly after the breakdown of a pricey partnership between IBM and MD Anderson Cancer Center that was focused on incorporating the tech into hospitals.

Developing the skills

IBM Watson isn't the only AI technology available: $3.6 billion has been invested across 481 healthcare AI deals from the first quarter of 2013 through the first quarter of 2018, according to consultancy CB Insights. More than 150 healthcare AI start-ups have raised their first equity rounds since January 2016.

Healthcare AI work has predominantly focused on uses in imaging and diagnostics, according to CB Insights, but clinical insights and risk analytics, as well as clinical trials and drug discovery have also attracted a lot of funding.

"I think we're moving toward an era where you don't need to own all the skills, you just need to have all the skills. It is going to be a much more agile ecosystem of operation. And you see pharma is already starting to recognize that through the types of deals and collaborations that they are doing," said Spence.

In mid-2017, GlaxoSmithKline said it paid $43 million to link up with AI start-up Exscientia. Sanofi announced a deal with the same company a month earlier. Meanwhile, AstraZeneca inked a deal with Massachusetts AI start-up Berg to aid in target discovery. Both Takeda Pharmaceuticals and French pharma Servier have struck deals with AI-based drug design firm Numerate.

AI isn't all being done through collaboration, though.

"There is going to have to be a balance," argued Sean Rooney, a partner in PWC's advisory services, in an interview. "AI is not just going to be accepted and adopted by the industry, by the scientists, by branded commercial managers, if it is a black box. So [pharma is] going to need to have enough onboard capability, and substantiated knowledge and experience within the organization to explain and understand what might be happening within 'the machine' to explain the output."

Pfizer is one of the companies doing just that; the big pharma has said AI is a strategic focus and is working to develop its own in-house capabilities.

The New York pharma is using AI to support a number of its drugs, both in development and those on the market.

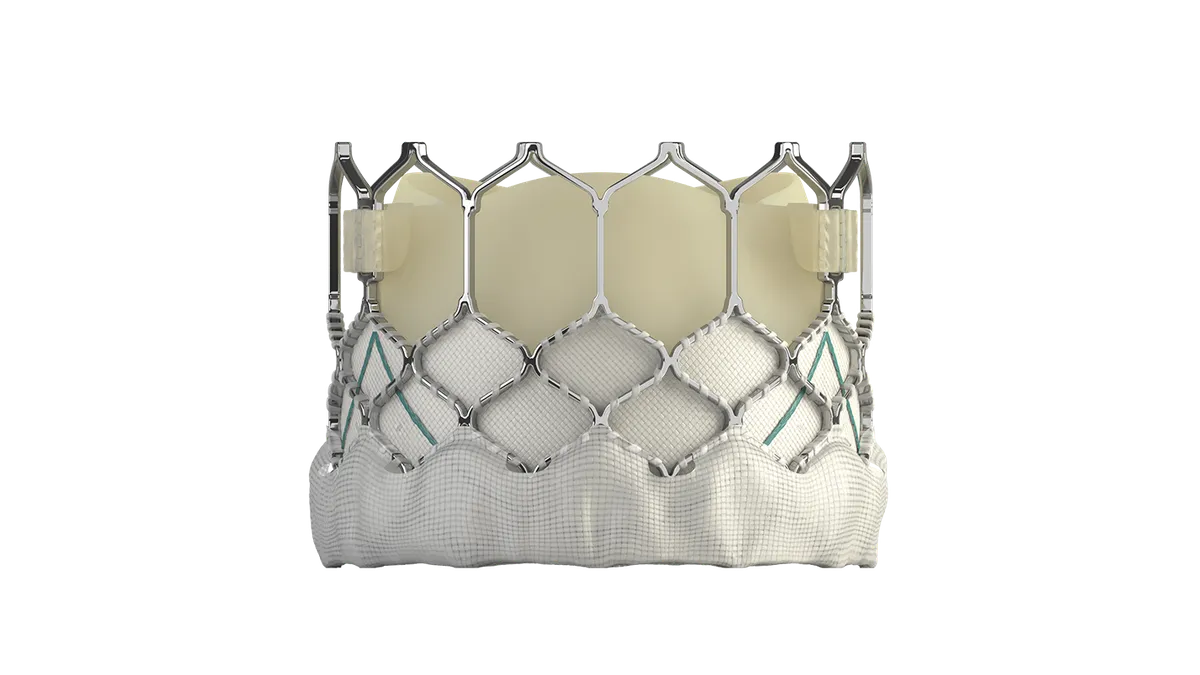

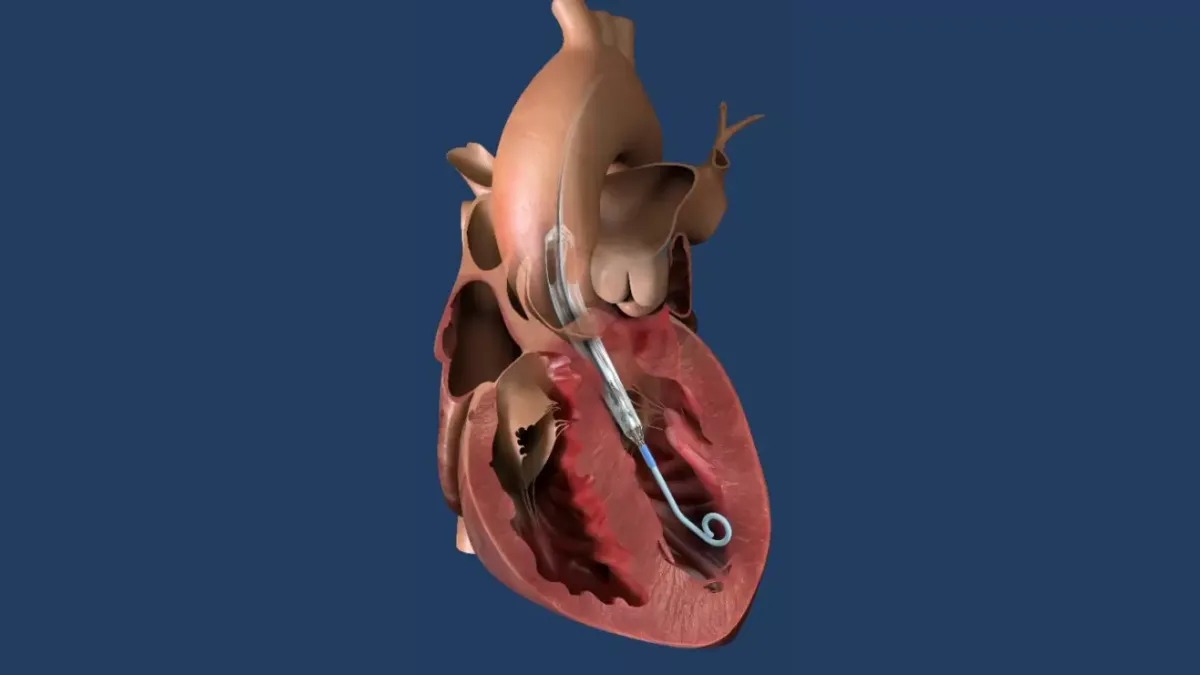

For example, the company has been using AI to sift through millions of electronic medical records to identify clinical markers that could point to a diagnosis for a rare form of heart disease called transthyretin cardiomyopathy (TTR CM).

"What machine learning and artificial intelligence allows us to do is explore millions of different comorbidities, lab data, procedures, physician notes, graphics, and allows us to build models that could potentially identify these patients," said Julie Schiffman, VP of business analytics at Pfizer, in an interview.

"This data is de-identified to Pfizer at a patient level, but what it enables us to do is potentially educate the physician communities about symptoms to look for to see if their patients have TTR CM."

"It also allows us to think creatively about how to work with providers and payers to help them to identify patients that might be at risk in their communities."

On the commercialization end of the spectrum, Pfizer has used the technology to better market one of its existing drugs — the smoking cessation product Chantix (varenicline).

"We know that when patients start and successfully complete an appropriate treatment regimen [generally], that's really fundamental in driving better health outcomes," Jeff Hamilton, SVP of business technology at Pfizer, said in an interview.

Pfizer is using public data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and IMS, Hamilton said, as well as other public data sets and de-identified data to find patients that have successfully quit smoking. The pharma then uses that data to identify patient segments that are more likely to quit successfully. "We are now using that information to reach similar patient populations and communicate the benefits of smoking cessation," he added.

But will it work?

One of the biggest hurdles to the inclusion of AI in drug development is validating that it actually works. Rooney pointed out that clean, robust, large data sets are key to this technology coming to appropriate conclusions.

Validation can come in many forms though — some that have to hold up to regulatory scrutiny, and others that just make good business sense.

Schiffman noted that when judging the productivity of AI in discovery and R&D, Pfizer looks at things like whether it can pinpoint more targets than it would with traditional methods, if the cycle time of drug development has been reduced and whether it can improve attrition rates.

Other programs though, require different forms of validation. Using the same smoking cessation program that Pfizer conducted, Hamilton said that Pfizer ran a parallel market research program to verify the outcomes and the data.

In the TTR CM program, Pfizer is having discussions with key opinion leaders to share the algorithms and discuss the characteristics found to ensure that it translates into what is actually seen in clinical practice.

"Because this is such a new space, it's about making sure that the conclusions we're finding [are accurate] and pressure testing them as robustly as we can, whether that's through market research or work with our KOLs. But our hope over time though is that we will build our confidence in these areas," said Schiffman.