A nagging cough is one of the most common reasons people visit the doctor. An estimated 10% to 20% of Americans struggle with a chronic cough, yet it isn’t widely measured or monitored like other health indicators such as weight or blood pressure.

Joe Brew, an epidemiologist and data scientist turned entrepreneur, co-founded Hyfe three years ago to fill what he views as an information gap on this common medical symptom. Brew believes the company’s AI-powered cough-tracking technology can help patients and their doctors uncover the root cause of a cough. The acoustic AI is designed to detect and classify coughs.

Wilmington, Del.-based Hyfe plans to seek clearance from the Food and Drug Administration to market the technology as a medical device and has partnered with pharmaceutical company Merck to use the cough tracker in its consumer education efforts.

This interview has been edited and condensed for ease of reading.

MEDTECH DIVE: What gave you the idea to pursue development of a cough-tracking device?

BREW: It really emerged from the problem of coughing being the world's most prevalent clinical symptom. The main thing that people show up at the doctor's office for in just about every country on Earth is cough. Despite that, and despite everything else in medicine constantly being measured and quantified, you go to the doctor, they stick a cuff on your arm to get your blood pressure, they stick a thermometer in your mouth to get your temperature, they get you on a scale to get your weight, they measure your height, they look at your blood glucose, they literally put a number on everything. But when you go to the doctor with a cough, as we all probably have done at some point, what do they ask you? “How's your cough?” You, the patient, don't know.

And the reality is, nobody knows, just like you don't know your blood pressure. It's an amazing gap in the understanding we have of ourselves, and then the understanding that doctors have of ourselves. Self-report is not totally useless, but it's certainly not the most accurate way to do precision medicine, and in some cases, especially for very vulnerable people, self-report is totally useless. Think of an infant with pertussis, or an elderly person in a managed care facility who can't cognitively keep track of their coughing and perhaps can't communicatively express to a caretaker, “Hey, my cough is getting worse or better.”

How can your technology assist doctors in diagnosing and monitoring health conditions?

Literally we want to count your cough. We also figuratively want it to count. We want it to be one other thing in your medical history and your wellness report, and your own understanding of your body and your symptoms.

That huge gap is what we're trying to fill, and the way we're doing it is with this company Hyfe, which is focused on cough detection and cough quantification. We think it's kind of revolutionary. What we want to do is get doctors actionable, useful, objective, accurate medical information. And my experience interacting with doctors about cough counting is, it is universally attractive and interesting to them. They all say, “I would like to know how many times and when my patients are coughing.”

What respiratory illnesses does the technology address?

When we started, a lot of us were health researchers and entrepreneurs. We came from a health background and focused on infectious disease like tuberculosis. But then COVID started, and suddenly cough was on everybody's radar. And people began to realize coughing really matters, and we don't know much about it. And meanwhile, we stumbled, I would say, into the world of chronic cough, which affects 10% of all adults, and where cough is not a symptom of the problem, cough is the problem itself. Chronic cough is often over-sensitivity. And so now a lot of our focus is serving chronic coughers because they're just a totally neglected population. There are very few therapeutics for them. So we're generating evidence that helps them understand themselves and helps their practitioners to better treat them.

Is it a wearable device? How does it work?

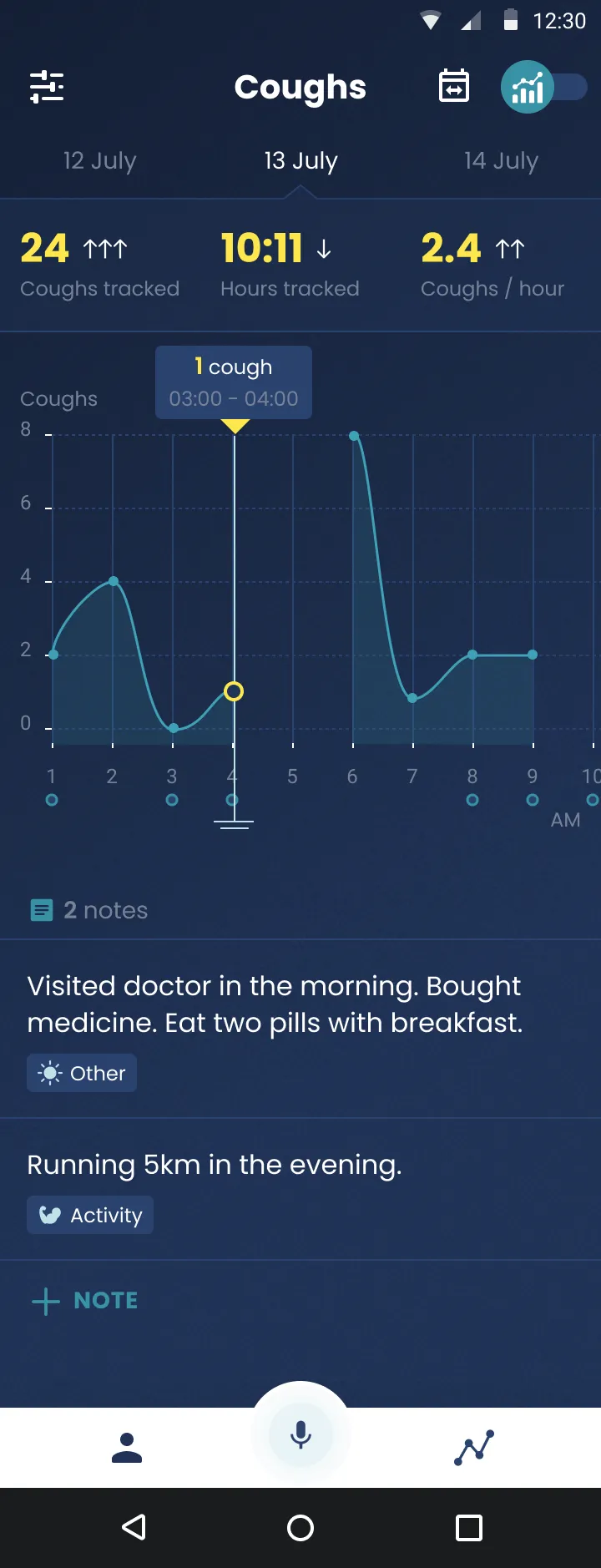

Our primary capability is a model that we called Allison. And she's called Allison because she's always listening. Allison can be deployed in a number of modalities. It can be deployed on wearables like watches, and in fact we build our own cough monitor watch, which the patient wears, and it counts their coughs. It can be deployed in other computers like smartphones, and we have an iPhone app and an Android app called Cough Tracker in the United States and Cough Pro elsewhere. And that also runs Allison. And then it can be deployed on other modalities such as a desktop computer, so if you’re going to do workplace monitoring. Is this a wearable? Yes, and it's also other things. We really like the wearable, because we think there's a lot of value in continuous monitoring, 24-hour cough tracking.

The phone apps are free and on the market globally. So you can go right now on your iPhone or Android and look up Cough Tracker or Hyfe and download, and in one minute you can start tracking your coughs. The reason that’s free is because it allows us to learn a lot about how people use cough, how much people cough, what kind of valuable things people want from cough tracking. It allows us to train models on that data. So, you know, your cough sounds different from Christy's cough. So to collect that data is really useful for us.

Cough Monitor is a wearable that we have built. It's in clinical trials right now. We're submitting to the FDA for clearance this year as a medical device. So that's not available on the market, but patients are wearing it, and we're testing it and trying to show that it accurately detects cough. Cough Watch is a very similar product that is available to researchers but not to the general public.

What have researchers learned in clinical trials using your cough tracker?

A really fascinating one (is) a study published in just the last couple of weeks among those with tuberculosis. Tuberculosis is notoriously difficult to diagnose. People are underdiagnosed, people are overdiagnosed, you have a ton of mistreatment. It's six months of chemotherapy, so it's a really big deal if you get the wrong diagnosis. We saw a group of independent researchers track coughs among those with TB and found a drastic reduction in cough at the immediate initiation of treatment, which is great, because it shows that the drug matches the bug, which is a really big deal, especially with antibacterial resistance. It's an indication that those patients were correctly treated. They also found that those with TB had significantly higher cough rates than those with other infectious disease. That's really important for screening because TB is a massive pandemic. If you can just find those missing people via cough rate, that's very low hanging fruit, it scales infinitely.

We have some research projects that are showing that GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease) is underdiagnosed as well. If you have reflux, it triggers your throat sensitivity and you cough, and it corresponds with meal times. And then perhaps one of the most interesting ones came out a couple months ago. A study done at the Emerging Pathogens Institute at the University of Florida tracked cough among those who had severe COVID, and they found that a decrease in cough frequency was prospectively associated with negative outcomes, so intubation or death, and this was super counterintuitive. It makes some biological sense that maybe as your organs begin to fail, your body is perhaps diverting resources from high-caloric-expenditure activities like cough to keeping your heart pumping or your lungs breathing. In the future, you can imagine a scenario where you would monitor coughs of patients and you would see that coughs have gone down over the last few hours, let’s get her on oxygen and steroids because it looks like she's going downhill, and maybe you could save a life.

What’s next for Hyfe?

So the order here is, you build a device which allows you to measure. Once you measure, you can generate clinical evidence. Once you generate clinical evidence, you can then incorporate it into clinical best practice. But we don't want to rush it, we don't want people to make decisions based on a completely new measurement, until we have really robustly shown the science. That’s why we're really delighted that we are in over 30 trials right now of different independent researchers who are counting coughs of those with COPD, asthma, chronic refractory cough, pediatric cough, tuberculosis, even malaria, showing what cough is like in these patients. And a lot of those trials in the medium term are going to translate into actionable clinical guidelines.

There are a couple of important milestones in our journey. One is, of course, getting FDA clearance, because then we can market ourselves as a medical device. And that opens the gates for practitioners being able to use this at scale. Right now the trials are undergoing, and we’ll have analysis results by the end of next month. We will submit in the middle of 2023. We expect clearance, optimistically, by the end of 2023, realistically just based on FDA timelines, probably Q1 of 2024. That's for the medical use case, which we think is really important and where we're going to have perhaps the most important impact.

There's also the wellness use case. If you're busy, you're occupied with your work, your kids, your family, your responsibilities, you might not be paying attention to the fact that wow, your cough has increased 150% or 300% in the last 24 hours. A device can easily handle that for you without the cognitive load. And it's really interesting. Imagine a world where it notifies you to say, “Hey, heads up, you're getting sick. You haven't felt it yet, but it's time to take a chill pill.”