The Food and Drug Administration on Tuesday released two final guidance documents that would loosen regulations for certain types of wellness and software products.

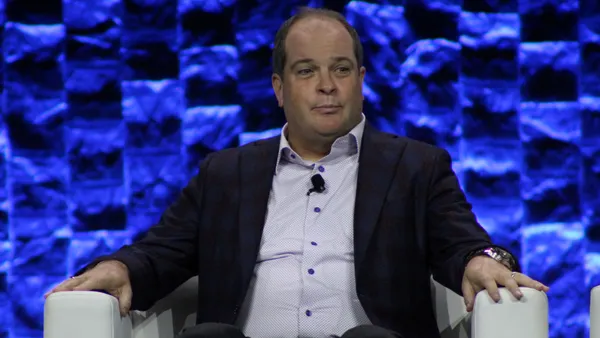

FDA Commissioner Marty Makary announced the changes at the Consumer Electronics Showcase. Makary, in a video posted on X, said the changes would “promote more innovation with AI in medical devices.”

Wellness exemptions for blood pressure, blood glucose

The first guidance clarifies the FDA’s thinking on what constitutes a wellness device. It offers broader leeway to wearables that provide readings around heart rate, blood pressure and blood glucose, so long as they are intended solely for wellness purposes.

In examples provided in the guidance, the FDA said a wrist-worn wearable that tracks metrics including sleep, pulse rate and blood pressure would fall under a general wellness claim, provided the product has validated values for blood pressure.

The guidance appears to contradict a warning letter the FDA sent to wearable company Whoop last year for rolling out a blood pressure feature without authorization. At the time, the agency said that blood pressure is inherently related to a medical diagnosis.

A spokesperson for Whoop applauded the new guidance in an emailed statement, saying it clarifies that Whoop can provide blood pressure insights and wellness metrics when designed for non-medical purposes. The spokesperson said the changes should “help resolve long-standing uncertainty about the boundary between providing wellness insights and medical diagnosis and treatment.”

Another example was for a wearable intended to provide blood glucose estimates to monitor nutritional impacts, and is explicitly contraindicated for use by people with diabetes and pre-diabetes. According to the guidance, this would fall under a general wellness claim, but would not count as a low-risk product if the device used microneedle technology to provide the estimates.

In 2024, the FDA warned consumers not to use smart watches or smart rings that claim to measure blood sugar without piercing the skin.

“In the past, the FDA has permitted some measurements like pulse rate and O2 saturation in some wellness products, but not others,” Makary said in a speech at CES. “It didn’t always make a lot of sense from the outside.”

Tom Hale, CEO of Oura, maker of a wearable ring that is working on a blood pressure feature, welcomed the changes in a LinkedIn post.

“As wearables continue to evolve, modern regulation that recognizes the difference between early awareness and medical diagnosis is critical,” Hale wrote.

Less regulation of clinical decision support software

In a separate guidance, the FDA unveiled significant changes to how it regulates clinical decision support tools. The biggest change is to a section describing how the FDA interprets whether software is providing recommendations to healthcare providers. Software that provides a sole medical recommendation can now be exempt from regulation. Under a previous guidance, it would have been considered a medical device.

For example, according to the new guidance, software that predicts a patient’s risk of future cardiovascular events based on their weight, smoking status, blood pressure and lab tests would be exempt from FDA enforcement. However, if the same test was intended to predict the risk within 24 hours, or used genomic data, it would be considered a medical device.

Another example considers the use of software to summarize radiologists’ findings, a concept that firms are testing using generative artificial intelligence. A software function that analyzes a radiologist’s report to generate a summary with specific diagnostic recommendations would be exempt. However, if the software directly analyzed an image to create the report, it would still be regulated by the FDA.

The guidance also spells out what information device makers must provide to clinicians so they can review the basis of the software’s suggestions. Software intended for critical, time-sensitive tasks would still be considered a device, and companies should provide a description of the underlying algorithm, validation and required input information, the FDA said.

The pair of guidance documents offers some insight into the Trump administration’s approach to AI. In past months, the administration has pushed for a deregulatory approach, but with few details. The Department of Health and Human Services issued a request for information to the healthcare industry in December, asking for feedback on how the department can help speed adoption of AI.

Both documents were published Tuesday without a public comment period, an approach the Trump administration has recently taken for major policy changes.