Amid a deregulatory push by the Trump administration, the Food and Drug Administration is scrutinizing its digital health policies. The agency suddenly issued a pair of guidances earlier this month, intended to clarify its approach to wellness devices and medical software.

The updates reflect changes to the agency’s thinking about what counts as a wellness device, but also raise new questions and pose challenges to consumers, experts said.

FDA Commissioner Marty Makary announced the pair of guidances — issued without any prior notice or public comment period — at the Consumer Electronics Show in early January. Makary said the agency has 27 different guidances that deal with software and digital health, and he aims to cut that number by at least half, while updating them to be more clear, modern and consistent.

Despite Makary’s framing, attorneys viewed the updates as less of a major change to regulations, and more as tweaks and examples.

“He was talking about cutting red tape and deregulating, and that’s not really what these are,” said Amanda Johnston, a partner at Gardner Law. “The law itself has not changed.”

Wellness guidance clarifies requirements for wearables, but muddies the water for patients

The FDA’s guidance on wellness products had the most significant changes of the two, experts said. The document was focused on wearables, “which aligns with what we’ve heard from this administration more broadly,” said Scott Danzis, a partner at Covington. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has repeatedly emphasized wearables as part of his agenda, calling for everyone in the U.S. to wear one.

The most notable change to the guidance is that it specifies products derived from certain measurements, such as blood pressure or blood glucose, don’t have to be regulated as medical devices if they are used for wellness. The position is a reversal from a warning letter the FDA sent to wearable company Whoop in July, saying that blood pressure measurements are “inherently associated with the diagnosis of hypo- and hypertension.”

“This guidance, to me, pretty clearly signals that that is not their position anymore,” said Claire Davies, a shareholder with Polsinelli.

The change provides helpful clarity for developers, Davies added, but will likely result in more products coming to market without FDA review.

For patients, differentiating between products that have been authorized by the FDA and those that fall under the wellness exemption can be challenging.

“They’re counting on savvy consumers to be able to understand the difference, where I don’t think that’s always the case,” Gardner’s Johnston said.

It will be important for patients to look at the labeling or marketing claims of devices, said Priyanka Shah, a principal project engineer in device safety at ECRI, a nonprofit focused on healthcare safety. If the label at any point says wellness, Shah added, the device should not be used for diagnostic purposes.

Shah compared it to the use of pulse oximeters during the COVID-19 pandemic to track blood oxygen saturation. Many pulse oximeters sold in stores or online are not medical grade or FDA cleared. Concerns about the accuracy of unregulated, over-the-counter pulse oximeters came up in a 2024 advisory panel.

“They can just mention in their labeling that this is for sports or recreation purposes, and that will completely take that product off that FDA regulatory pathway,” Shah said.

When can wearables tell people to see a doctor?

Another significant change in the wellness guidance was that wearables can now direct users to seek an evaluation by a healthcare provider if they get a reading outside of ranges appropriate for general wellness use. The act of telling someone to see a doctor wouldn’t make a product a medical device.

“I think it’s important that under this guidance there is an opportunity to say to the user, you should get checked out, but how you go about doing that is a tricky question,” Covington’s Danzis said.

With the changes, for example, if a person had a low oxygen saturation reading, their device could tell them to talk to a clinician, Danzis said.

The challenging part is that the FDA does not define the limits around what ranges are appropriate for a general wellness use, Polsinelli’s Davies said. Additionally, the guidance says that for products to fall under the wellness exemption, they cannot name diseases or conditions, or characterize an output as abnormal or concerning.

“One of the open questions is how do you do this in a way that is appropriate but also useful?” Danzis said. “If you or I were using a tool, and you get a notification saying that you should talk to your doctor, about what?”

Questions about clinical decision support

The FDA also published guidance this month that makes some changes to how it regulates clinical decision support software. While the base criteria for what counts as clinical decision support, or CDS, has not changed, the FDA made a few tweaks to when CDS falls under enforcement discretion.

Under previous guidance, software could not provide a sole recommendation, such as a drug or a diagnosis for a patient, and be exempt from medical device regulations, Davies said. Under the new guidance, it is ok to provide only one recommendation if it’s clinically appropriate.

Davies said the change was a useful clarification, but it’s unclear what the standard is for there only being one clinically appropriate option.

One example provided in the guidance says that software that predicts a person’s risk of future cardiovascular events based on their weight, smoking status, blood pressure and test results would fall under enforcement discretion. However, the same device, if predicting a person’s risk of a cardiovascular event over 24 hours, would fall under FDA oversight.

This timing element is not new, Danzis said, but the way the FDA has framed it in the latest guidance raises some questions. If the software were to make a prediction for the next week, or the next year, he asked, would it be regulated as a medical device?

Questions about future AI regulations

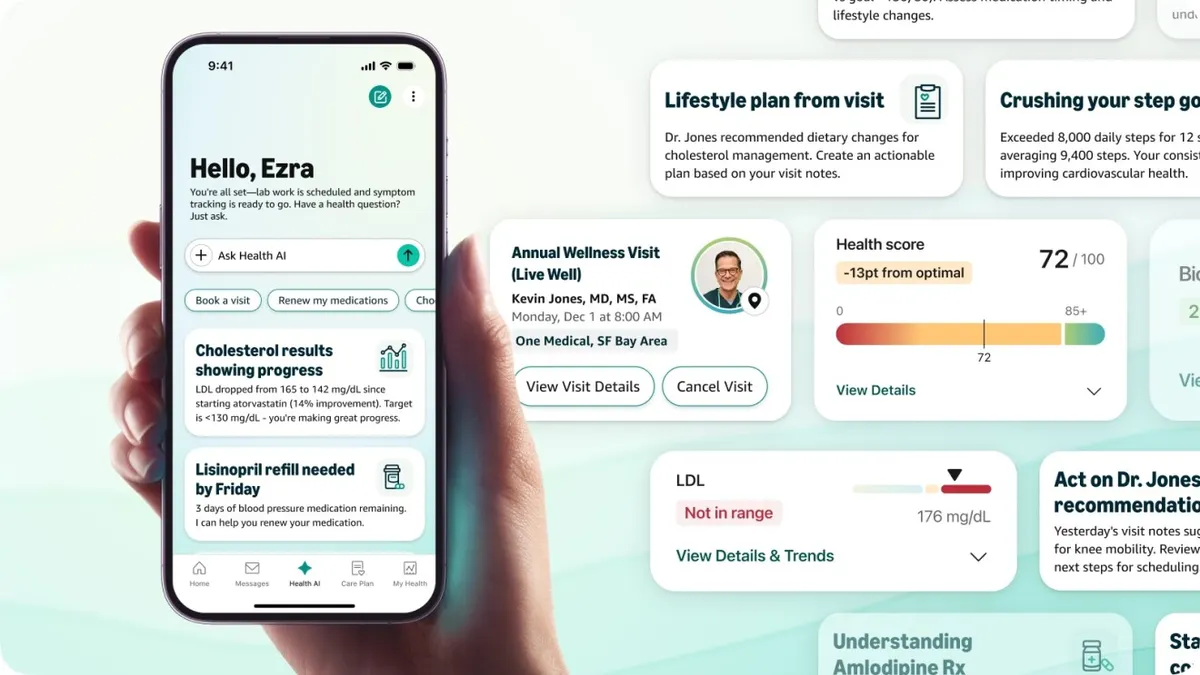

When Makary announced the two guidances in a post on X, he said they would “promote more innovation with [artificial intelligence] in medical devices.” The documents themselves don’t say anything new about AI, Davies said, although CDS is relevant for people who are developing AI products.

The industry is waiting for an update after two digital health advisory committees discussed generative AI and the FDA received comments on how the agency should monitor the real-world performance of AI in medical devices.

“There is also just this huge waiting game for when and how FDA is going to regulate or authorize for marketing a gen AI-based product,” Davies said.