A near-death experience with hemorrhage left a scientist searching for ways to detect serious blood loss early.

Kelsey Mayo was sitting at her desk in 2019 when she passed out from severe pain. She had an ovarian cyst that ruptured and was bleeding internally.

After her colleagues rushed her to the emergency room, Mayo’s symptoms were initially dismissed. She ended up receiving an emergency blood transfusion and emergency surgery after a medic, who was passing by, listened to her.

The experience reminded Mayo of a conversation from years prior when she was studying for her PhD in material science at Vanderbilt University. Her friend had raised the problem of postpartum hemorrhage, which is the leading cause of maternal death globally, but is also largely preventable.

“I was shocked,” Mayo said. “As an engineer, that felt unacceptable, and it also felt very solvable.”

Mayo and her friend, Christine O’Brien, agreed that solving this problem would be their dream job.

In 2022, after Mayo’s near-death experience, they co-founded Armor Medical.

“That lived experience really is what gives me the fire in my belly, together with all the stories from folks I've talked to who have survived hemorrhage,” Mayo said.

O’Brien and co-founder Leo Shmuylovich, both assistant professors at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, had developed a working prototype of a wearable that can detect early signs of hemorrhage. The wrist-based device uses a laser and a camera to quantify flowing red blood cells.

In addition to preventing deaths, detecting signs of hemorrhage early can help avoid the need for blood transfusions, hysterectomies and long ICU stays, Mayo said.

One challenge is that early blood loss is often silent. Vitals can appear normal until a patient has lost more than a liter of blood, according to Mayo. Common methods of detecting postpartum hemorrhage, like visual estimates or weighing blood-soaked pads, can be delayed or inaccurate.

When the body recognizes it’s losing blood, it will clamp down on blood vessels in the periphery, such as the hands and feet, to push extra blood supply back to the vital organs, Mayo said. Armor Medical’s device keys into these early changes.

Another challenge with hemorrhage is that many patients, about 40%, have no prior known risk factors, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

“That's why we are really interested in having this be available to all mothers, regardless of their risk status in the beginning,” Mayo said, “because too many moms fall between the cracks.”

Funding and future plans

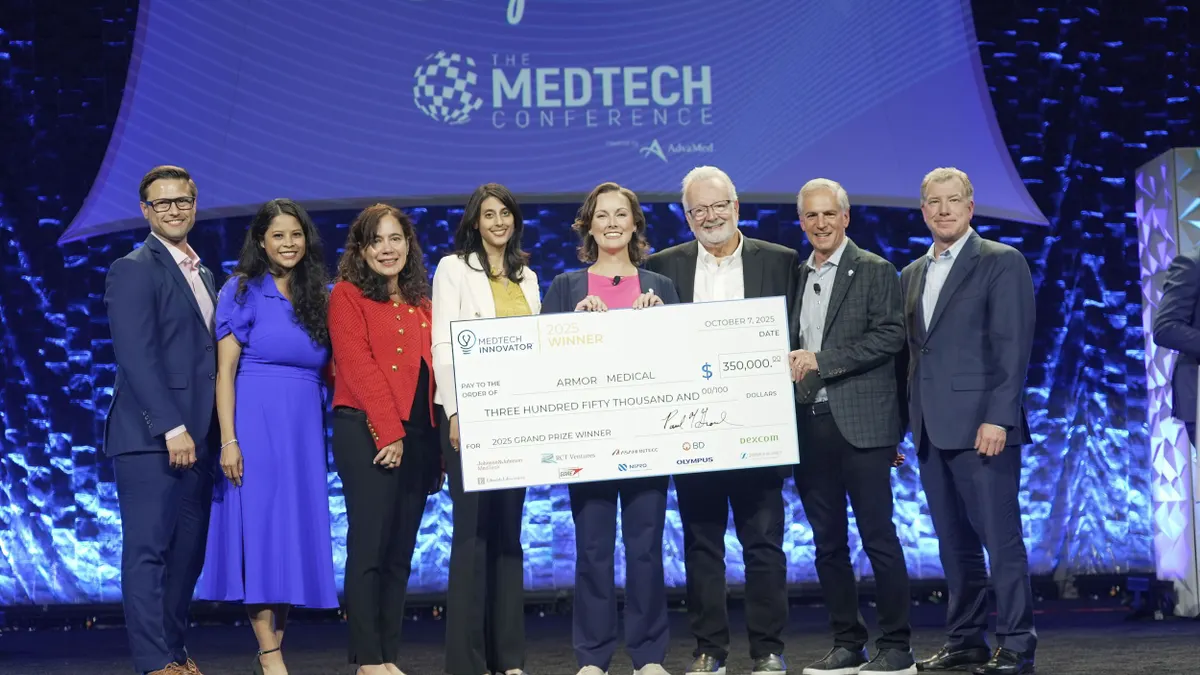

Earlier this month, Armor Medical won MedTech Innovator’s Early Stage pitch competition at AdvaMed’s The MedTech Conference and received a $350,000 cash prize.

“I don't take it for granted that we've had a lot of success lately, and I really wish the same success on my cohort as we're all getting slammed with [National Institutes of Health] money getting dialed back,” Mayo said. “It's just hard times.”

Mayo said that Armor Medical has refined its prototype, and that early feasibility studies have shown the device can detect concerning blood loss five times earlier than the current standard of care, and it can do so accurately across different skin pigmentations. Armor Medical plans to use some of the prize money to fund a clinical trial next year, and the company is also working on a 510(k) submission for the Food and Drug Administration.

“You have to be balanced between being a risk taker and being smart with your money, because in today’s environment, money is hard to come by,” Mayo said. “We understand that there is added risk right now with timelines, and we are preparing for it.”

Armor Medical is also raising a $5 million funding round to support the clinical work. The company hopes to bring its device to market in early 2028.

The company plans to sell its device to hospital systems, including regional perinatal care centers, and rural and urban hospitals that see many high-risk patients. Patients would wear the device while in the hospital and receive some educational material. However, their healthcare provider would be the main user.

Mayo envisions a version of the device that is prescribed to go home with parents. Her company has been engaged in conversations with patients, midwives, doulas, nurses and OB-GYNs to find a balance of what information patients might want at home while still knowing that their healthcare provider would need to be involved.

The CEO added that she wants people going through childbirth to be informed without the technology feeling like a distraction.

“Moms want to focus on their baby and their birthing experience,” Mayo said. “And so we've, we've been very thoughtful about, How do we center the patient? What can we do to make their experience better?”