GE Healthcare, Medtronic and Philips are among the big medtechs investing in artificial intelligence and machine learning, technologies they contend hold potential for better diagnosing, managing and treating a wide variety of diseases and health conditions.

While medtechs are only starting out on their AI/ML efforts, they are developing, acquiring and implementing these technological capabilities, betting it will put them ahead of rivals to ultimately drive future growth.

"One of our core differentiators is our ability to take cutting-edge technology and apply it to medical technology," including AI, Medtronic CEO Geoff Martha said in October at the company's investor day.

"With the emergence of big datasets, combined with innovation in robotics, sensors, computational power and AI, some of the greatest advances in medical technology are unfolding right now," Martha said.

Martha's marketing tagline is that Medtronic is "putting the tech into medtech," an initiative that includes several technologies supporting its spine surgery portfolio such as robotics, navigation, advanced imaging and pre-operative planning aided by AI. Some Medtronic technology has been developed internally, while others are through partnerships and acquisitions.

Last month, the giant completed its 7 euros-per-share tender offer for French spinal surgery specialist Medicrea, four months after announcing the deal. Medtronic's interest in Medicrea appears to be driven largely by the company's AI.

Among Medicrea's key products is its UNiD ASI pre-procedure platform for surgeons that the company says uses predictive modeling algorithms to measure and digitally reconstruct a patient's spine. Medtronic execs contend the future of spine surgery is driven not just by metal implants and instrumentation, but also by a series of enabling technologies including robotics, navigation, advanced imaging and increasingly pre-operative planning aided by artificial intelligence.

The Medicrea buy means Medtronic is able to tap an AI database of more than 5,000 surgical cases. With the acquisition completed, Medtronic claims it's the first company in spinal surgery offering AI-driven planning, personalized implants and robot-assisted delivery.

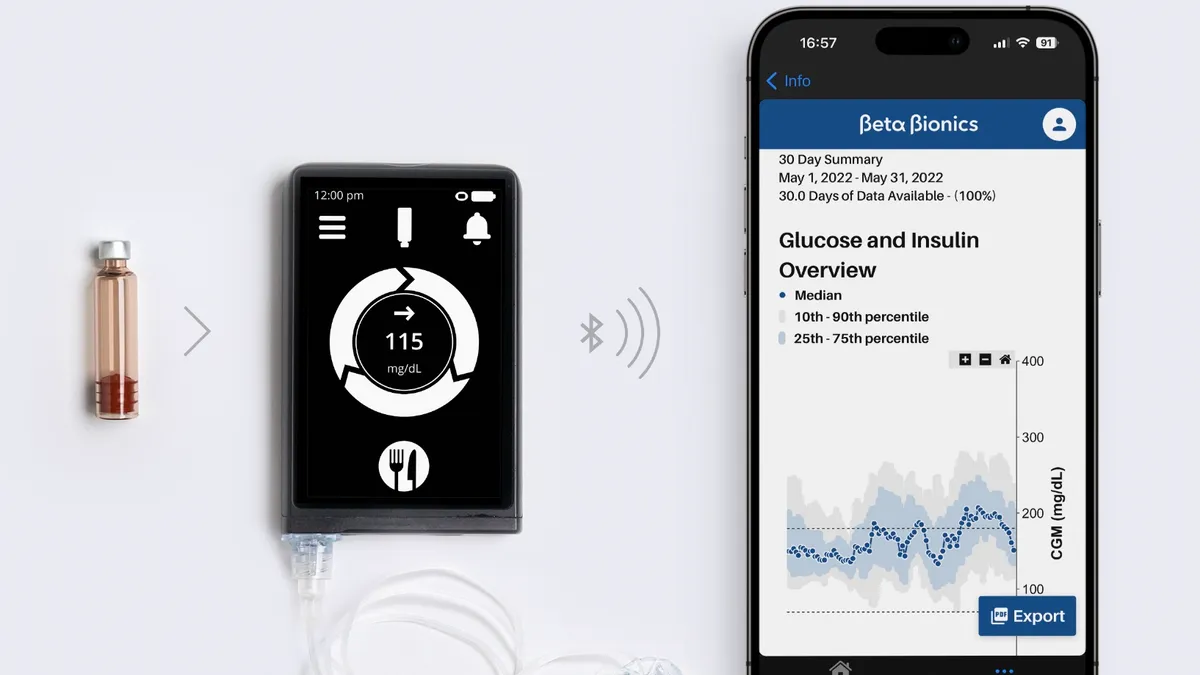

Similarly, Philips' strategy is to lead in health technology "on the back" of market trends such as "higher precision" diagnosis through AI and workflow informatics. The Dutch healthtech giant on Friday announced a $2.8 billion cash deal to buy Bio Telemetry, which specializes in remote cardiac diagnostics and monitoring, with portfolios in wearable heart monitors and AI-based data analytics and services.

Philips' Diagnosis & Treatment business is focused on growing its core of AI-enabled informatics to help clinicians identify actionable insights out of the tsunami of clinical data.

"We can innovate procedures to be more productive with better outcomes," Frans van Houten, CEO of Philips, said last month at the company's investor day. AI can drive "massive" productivity in healthcare and "unlock the value" of large amounts data, according to van Houten, by improving the use of limited existing resources and overburdened medical staff.

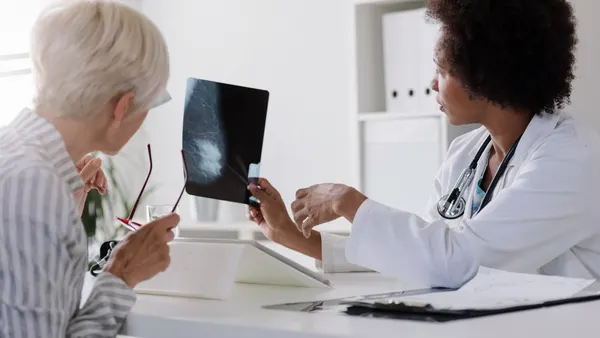

"In precision diagnosis in the world of radiology and pathology there is a lot of opportunity to drive a better, precise diagnosis," van Houten added.

Philips is putting a major emphasis on AI to give radiology customers a choice of algorithms to analyze medical images. Launched earlier this year, the company's IntelliSpace AI Workflow Suite features a set of applications for integration and centralized workflow management of algorithms that automatically analyze data without requiring user interaction. Apps from algorithm developers include Aidoc, MaxQ AI, Quibim, Riverain Technologies and Zebra Medical Vision.

The initial focus of the marketplace is on radiology, but Philips is looking to expand it to cardiology, pathology and other areas.

Likewise, GE Healthcare's Edison Marketplace is marketing to hospitals to test and buy the latest AI-powered software and algorithms from a range of third-party developers.

"We're working with third-party AI developers to address all the security, privacy and [application programming interface] issues, which may reduce the overhead that customers have," Ken Denison, vice president of digital platform and product marketing at GE Healthcare, said in a written statement.

Hospital customers will be able to take them for a "test drive" and evaluate the software using their own clinical datasets and medical imaging.

Edison Marketplace apps are meant to work within a hospital's existing workflow thanks to an Open AI Orchestrator that simplifies the selection, deployment and usage of AI in imaging workflows at scale.

"It will act similarly to smartphone software, but for the healthcare provider's network," Denison said. "It will be designed to channel the data from the systems of the hospital's CT scans, X-rays, MRIs, to the right app, so you will be able to just drop your algorithm into Edison Open AI Orchestrator and we’ll do all the plug and play."

Edison Marketplace is expected to host dozens of AI apps by the end of next year. In the meantime, apps are sold by GE Healthcare that include algorithms that can identify suspicious breast lesions in the grayscale images from ultrasound scanners and AI that can pick up on a collapsed lung in X-rays.

Lack of regulatory clarity on algorithms

While it is critical for medtechs to have a clear understanding of what medical technologies are considered AI based and which ones are regulated, currently there is a lack of regulatory clarity regarding machine learning algorithms that continually evolve, called "adaptive" or "continuously learning" algorithms, and don't need manual modification to incorporate learning or updates.

FDA to date has only cleared or approved medical devices using "locked" algorithms, which provide the same result each time the same input is applied to them and does not change. However, "nonlocked" learning algorithms are used in self-diagnosis consumer apps, according to a study published earlier this month in the Journal of Medical Internet Research. Alarmingly, the diagnostic efficiency of the such apps seems to worsen over time.

The two-year study evaluated four AI-assisted, self-diagnosis apps for three ophthalmology diagnoses (glaucoma, retinal tear and dry eye syndrome) and found that all the apps either worsened in their results or remained unchanged at a low level.

The author points out that FDA had previously excluded such apps from regulations that are usually applied to medical devices, but a 2019 agency white paper proposed possible changes in the regulation of self-diagnosis apps, differentiating between "locked" and ML-based learning algorithms, with the latter falling under a stricter set of proposed rules.

However, he observed that the "provided definitions of the two categories are still vague and rely on the manufacturer admitting the use of AI-based technologies rather than on hard criteria."

FDA is considering a total product lifecycle-based regulatory framework for adaptive or continuously learning algorithms "that would allow for modifications to be made from real-world learning and adaptation, while still ensuring that the safety and effectiveness of the software as a medical device is maintained."

However, it's been a year and a half since the FDA issued a discussion paper on its proposed regulatory framework for machine learning-based software as a medical device (SaMD) and the agency has yet to promulgate any regulations.

Tackling the topic does not seem imminent. The FDA put the AI/ML guidance on its so-called B List for documents that FDA "intends to publish as resources permit during FY2021."

A GAO/National Academy report last month noted that while the FDA's proposed total product lifecycle regulatory approach could allow devices to continually improve after they are in use and provide safeguards, the agency's framework is in draft form and is not intended to serve as guidance or regulations for developers of SaMD.

"Finalized guidance or regulations from FDA, including details and examples of what types of AI tools they cover, could improve predictability, so that developers better understand what will be required of them. In addition, knowing whether AI tools will be regulated as medical devices may provide insights into questions of liability," the report concluded.