Sometimes, the line between medical and wellness products can blur. Regulators’ pushback on a blood pressure feature that Whoop incorporated into its wellness wristband illustrates the challenges wearables developers face as they add increasingly sophisticated features.

Whoop received a warning letter from the Food and Drug Administration this summer after rolling out the blood pressure offering without regulatory authorization.

The company has pushed back on the warning letter, however, arguing that blood pressure is a wellness feature. The FDA disagreed, saying blood pressure is inherently related to a medical diagnosis.

The FDA isn’t likely to concede on its challenge, experts said. Whoop’s skirmish with the FDA offers lessons on where to draw the line between wellness and medical features.

Whoop’s conflict with the FDA

Whoop debuted its blood pressure insights feature in May. It uses heart rate, heart rate variability and blood flow patterns during sleep to estimate systolic and diastolic blood pressure ranges upon waking. Whoop offers the software as part of its most expensive membership plan, which also includes electrocardiogram and heart rhythm notifications.

Whoop has not backed down since it received the warning letter in July. The company has issued public statements and CEO Will Ahmed went on CNBC to defend the feature.

“We firmly disagree with the FDA’s claims that Blood Pressure Insights qualifies as a regulated medical device,” Whoop said in a summary of its response to the FDA shared with MedTech Dive. The company added that it does not believe it is within the FDA’s authority to regulate the product and it intends to continue to offer the feature.

In an interview with Bloomberg last month, Ahmed said conversations with the FDA have taken a “constructive” turn, and the company is working on a path forward.

“The fact that they think they can just add a blood pressure feature and do these things without getting them approved by the FDA, it’s just not going to happen."

Mark Gardner

Founder and managing partner of Gardner Law

Experts think the FDA will likely hold its ground.

“I just don’t think the FDA is going away,” said Mark Gardner, founder and managing partner of the Gardner law firm in Stillwater, Minnesota.

While Gardner is a fan of Whoop’s wearable wristband — wearing one during an interview with MedTech Dive — he expects Whoop to lose its challenge against the FDA.

“The fact that they think they can just add a blood pressure feature and do these things without getting them approved by the FDA, it’s just not going to happen,” he said.

Typically, the FDA sends warning letters as a courtesy, giving the company an opportunity to fix a problem identified by the agency. A company can choose to defend against a warning letter, Gardner said, but the FDA is usually right.

Following a warning letter, the FDA may escalate its enforcement by going to the Department of Justice, getting a search warrant and seizing the offending products, or using a consent decree to bring companies into compliance, the attorney added.

How the FDA regulates wellness features

The FDA has typically taken an enforcement discretion approach with wellness features. The 21st Century Cures Act, which passed in 2016, included a regulatory carve-out for wellness software.

For a product to be considered for general wellness, it must present a low safety risk to users and must not make claims that specifically mention a disease or condition, said Abeba Habtemariam, a partner at Arnold & Porter law firm in Washington, D.C. For example, a feature for stress management would not be regulated, but a feature for anxiety would be a medical device.

“It's also interesting to think about, if Whoop were to challenge FDA in court, whether FDA’s interpretation of that exception would stand up, because the Cures Act itself doesn't provide specific criteria for determining whether something is intended for a wellness use,” Habtemariam said.

The FDA did not respond to MedTech Dive’s request for comment on Whoop’s warning letter and the agency’s next steps.

Other blood pressure wearables hit the market

The fact that other wearable companies have received FDA clearance for blood pressure products could also make it harder for Whoop to claim its feature falls under the wellness exemption.

In July, shortly before Whoop received the warning letter, another company called Aktiia received the FDA’s de novo authorization for an over-the-counter, wearable blood pressure monitor that provides systolic and diastolic readings, although it requires daily calibration with a traditional blood pressure cuff.

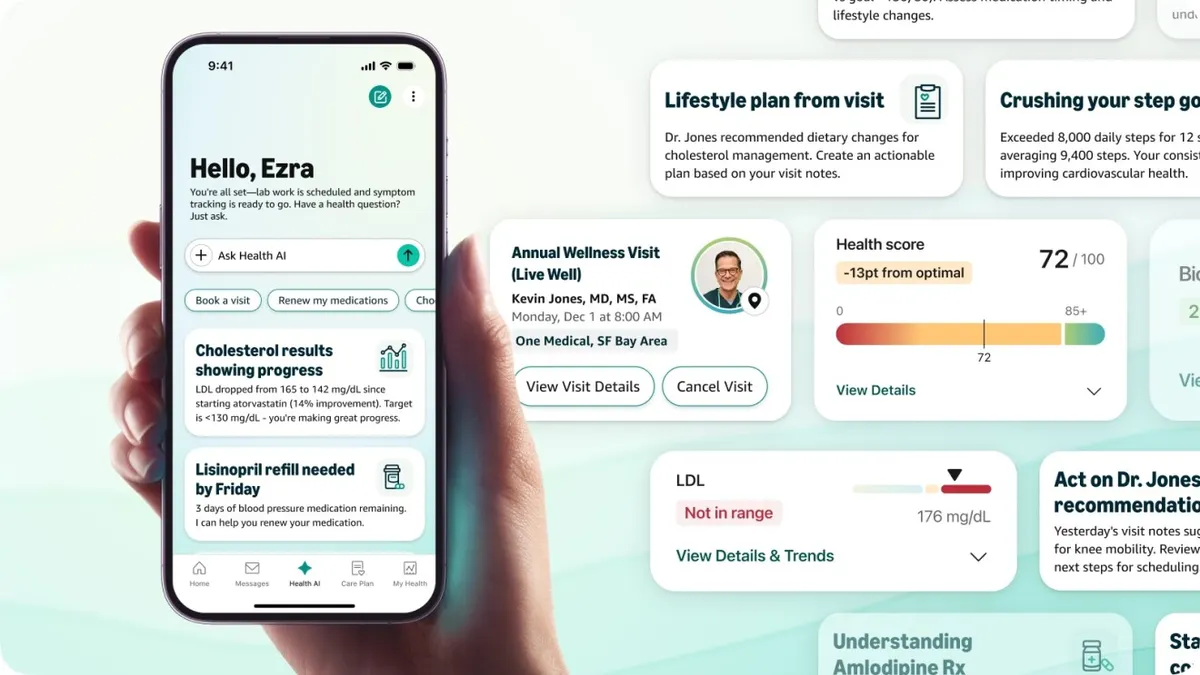

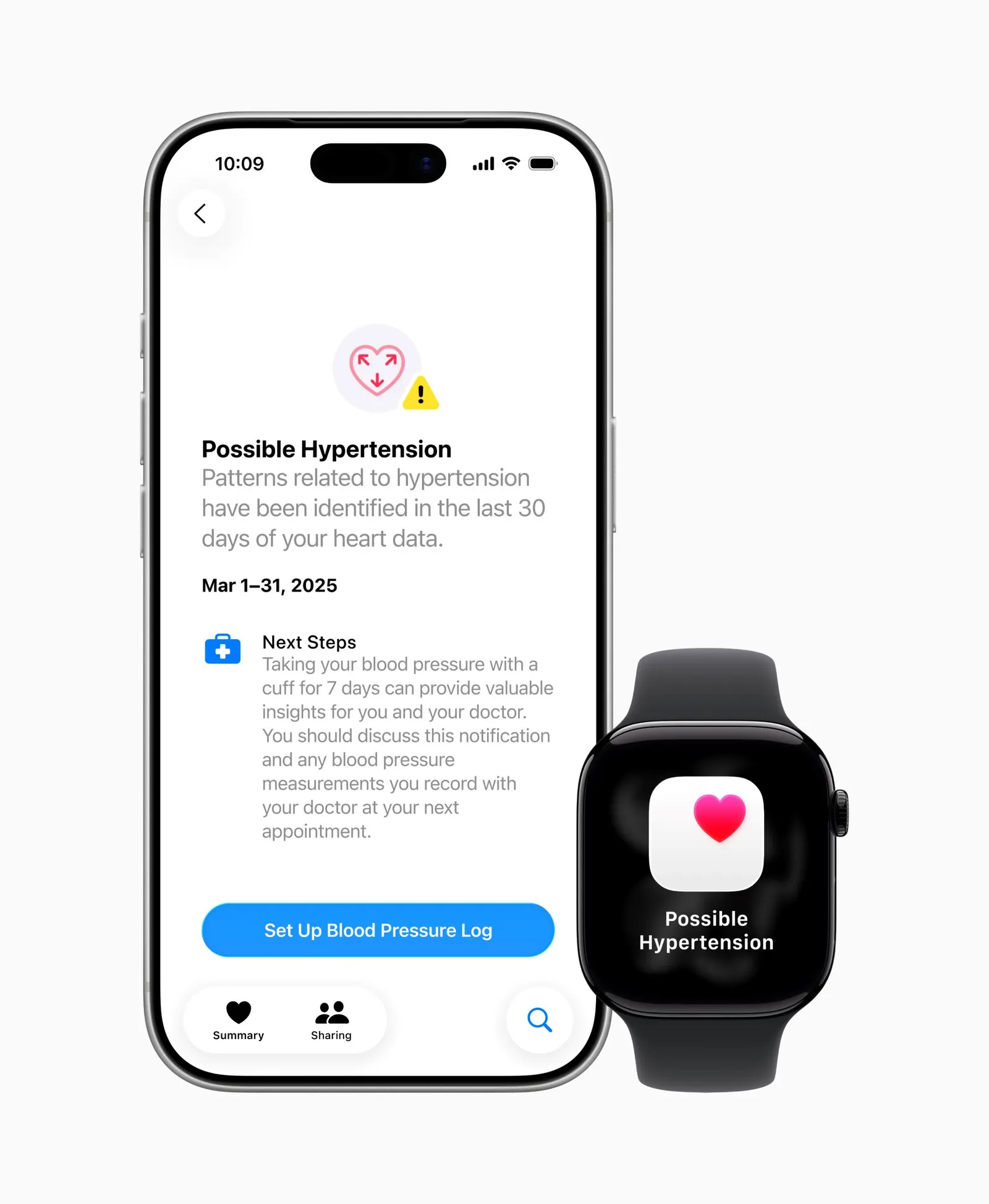

And in September, Apple received FDA clearance for a hypertension notifications feature for the Apple Watch, which analyzes optical sensor data over a 30-day period. Apple’s feature does not provide specific blood pressure readings, but users may receive an alert for “possible hypertension” instructing them to monitor their blood pressure using a cuff for a week and to talk to their doctor.

Apple’s clearance could be “a nail in the coffin” for Whoop, said Blythe Karow, founder of the Karow Advisory Group and writer of the Device Files. She added that it raises the question, if other companies have gone through the FDA, why wouldn’t Whoop apply for clearance?

Sometimes, the FDA will step up enforcement when a company in the same space is going through the agency, Habtemariam said. This is intended to level the playing field and encourage companies to pursue marketing authorization. For example, when Dexcom and Abbott were bringing the first over-the-counter continuous glucose monitors to market, the FDA issued a safety alert warning consumers not to use unauthorized wearables that claim to measure blood glucose levels without piercing the skin.

Similarly, the FDA issued a safety alert in September warning against using unauthorized devices for blood pressure measurement.

Even if Whoop’s blood pressure feature is accurate, offering it without going through the FDA could open the market to other products without scrutiny.

“How does FDA say, okay we’re going to let Whoop do this, but not this company that’s importing this product from somewhere else or whatever it may be,” Gardner said. “Ultimately, as a regulator, they have to regulate to the lowest common denominator.”

Cardiologists interviewed by MedTech Dive also indicated that they would steer patients toward devices that have gone through the FDA.

Vivek Bhalla, director of the Stanford Hypertension Center, said he directs patients to use blood pressure devices that are on the American Medical Association’s validated device listing. Currently, there are no cuffless blood pressure devices on the list, as the hypertension community is still working to develop validation criteria.

Blood pressure “should be treated with a high level of scientific rigor,” Bhalla said, adding that there’s a lot of downside to inaccuracy.

While he sees potential for cuffless blood pressure technology, Bhalla said the technology has some challenges, such as determining whether a person needs to have their arm in a certain position or to be still for the devices to be accurate.

“I believe in the near term future, we will have cuffless devices that hopefully will allow people to measure blood pressure for a period of time without sacrificing accuracy, and will be accepted by practitioners of hypertension,” Bhalla said.

Michael Curren, a cardiologist and professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, said it has become more common for patients to bring in some data from a wearable device, such as measuring their heart rate or rhythm. Hypertension is a little more challenging, because while traditional blood pressure measurements are easily reproducible and well understood, wearables use sensors and different algorithms to look at the changes in intensity of each heartbeat.

He said the technology still has the potential to be “incredibly impactful,” with patients able to come in earlier, check their blood pressure, and potentially start therapy sooner if a device flags potential hypertension. However, he also agreed that FDA authorization is important.

“Anytime something’s claiming to lead toward a diagnosis that hasn’t gone through FDA approval,” Curren said, “you need to be suspect of that.”

Lessons learned

Medtech and wearables companies can use a couple of tips to help determine whether a feature should be regulated as a medical device.

Gardner recommended reviewing plans with a lawyer early, as these types of decisions can affect FDA timing and investor expectations.

“That's where people get in trouble, because they told their investors … this product will be available by Christmas,” Gardner said. “And actually it won’t, because you have to raise millions of dollars to pay for the process of getting FDA approval.”

In other cases, clients approach the firm thinking their work makes them a medical device, when they actually fall under the exemption. Gardner said companies can provide a lot of information to consumers without becoming a medical device.

“The line isn't always clear,” he said. “It is gray.”

Arnold & Porter’s Habtemariam advised developers to closely watch the market to see if there are other FDA-regulated products that are similar to what they’re considering. If there are safety communications or recalls for those products, or if they have received clearance or approval, that would suggest that the FDA views them as regulated medical devices.

“The more enforcement there is from the agency, in some respects, I think it's helpful, because it provides companies with more guidance on where the line is,” Habtemariam added.

Finally, companies might find a competitive advantage in seeking out FDA clearance, Karow said. She advised wearables firms to hire or partner with people from the medical device industry who know how to get the level of clinical insight that’s needed to be effective.

Karow added that the wearables market is moving closer to diagnostics, as users are not satisfied with just wellness features.

“I do think that clinical validation and FDA clearance is going to be a moat,” she said.